On the prowl - conservation projects ensure wildlife in Brazil's Pantanal thrives

Cats are masters at tucking themselves into awkward and impossible spaces. But bigger cats are even better at finding ridiculous places to hide.

Ahead of me, two amber eyes peer from the hollow of a fallen tree trunk, its roots splaying outward like beams radiating from the sun. We’d been driving all morning in search of South America’s largest feline, but only here – deep in the cordillera forest – had we finally struck gold.

A wild, remote tropical wetlands in the heart of Brazil, the Pantanal is arguably the best place in the world to spot jaguars – although up until a few decades ago, it was almost impossible to see even a whisker rustling in the undergrowth.

Despite growing up in the sprawl of seasonally flooded savannahs and gallery forests, billionaire conservationist Roberto Klabin admits sightings were always extremely rare. But that didn’t deter him from transforming his family’s 53,000-hectare family cattle ranch into high-end lodge, Casa Caiman.

Thirty years later, it’s a very different story: in 2021, 99% of guests at Caiman saw a jaguar compared to 24% in 2014. Most visitors in 2022 (including me) are enjoying similar success.

Path less trodden

Getting to the Pantanal, an area larger than England, isn’t a quick journey. After landing in Campo Grande, capital of Mato Grosso do Sul, it took five hours to reach the property.

Tarmac turned into bumpy roads where armadillos scuttled below rickety fences and cowboys herded cattle through clouds of dust. My base for the next five days was Roberto’s former personal home, which was transformed into the 18-room Casa Caiman during lockdown (joining two exclusive-use villas, Cordilheira and Baiazinha, elsewhere on the ranch).

Testimony to the property’s feline focus, jaguar paraphernalia decorates communal areas. In bedrooms, photographs of saddles and cowboys are a reminder Caiman is still an authentic working ranch.

Nature walks, horse riding and game drives are all possible, but eager to discover more about Caiman’s ever-evolving conservation story, I spend my first few days with charity Onçafari, who have a base on site.

Pulling up in a customised sunshine-yellow Land Rover, plastered with rosette prints, founder Mario Haberfeld collects me just after dawn. Fronds of feathery donkey-tail grass glow strawberry-pink in the early morning light as we drive along shady trails listening to the guttural squeals of hyacinth macaws gliding overhead.

“I started Onçafari because I wanted to do something for Brazil’s wildlife,” explains Mario, a retired Formula 1 racing car driver, who’s travelled the world photographing iconic species ranging from pandas in China to polar bears in Canada.

“I wanted to develop ecotourism based on animal sightings, to prove to communities that a jaguar is worth more alive than dead.” Once widely dispersed throughout the Americas, jaguars have lost almost 50% of their historic range, largely due to loss of habitat and conflict with humans.

In the past, the predators have been perceived as a threat to precious livestock belonging to farmers who own 95% of the Pantanal.

Natural encounters

Inspired by a non-invasive habituation technique used with leopards in South Africa’s Londolozi safari camp, Mario and his team of professional biologists set about acclimatising jaguars to the sound of vehicles.

Using a cough to signal their presence, every day they would edge a little closer to the cats until the animals felt comfortable with cars at a reasonable distance. “It’s a natural encounter,” says Mario, insisting the animals are never fed.

“They don’t gain anything from it, and they don’t lose anything from it.” In 2012, Onçafari managed to collar its first cat, Esperanca (meaning ‘hope’ in Portuguese).

Holding aloft a telemetry device, while listening to a series of beeps through a receiver, biologist Pedro Reali tries to locate one of Caiman’s residents (eventually leading us to the aforementioned fallen tree trunk).

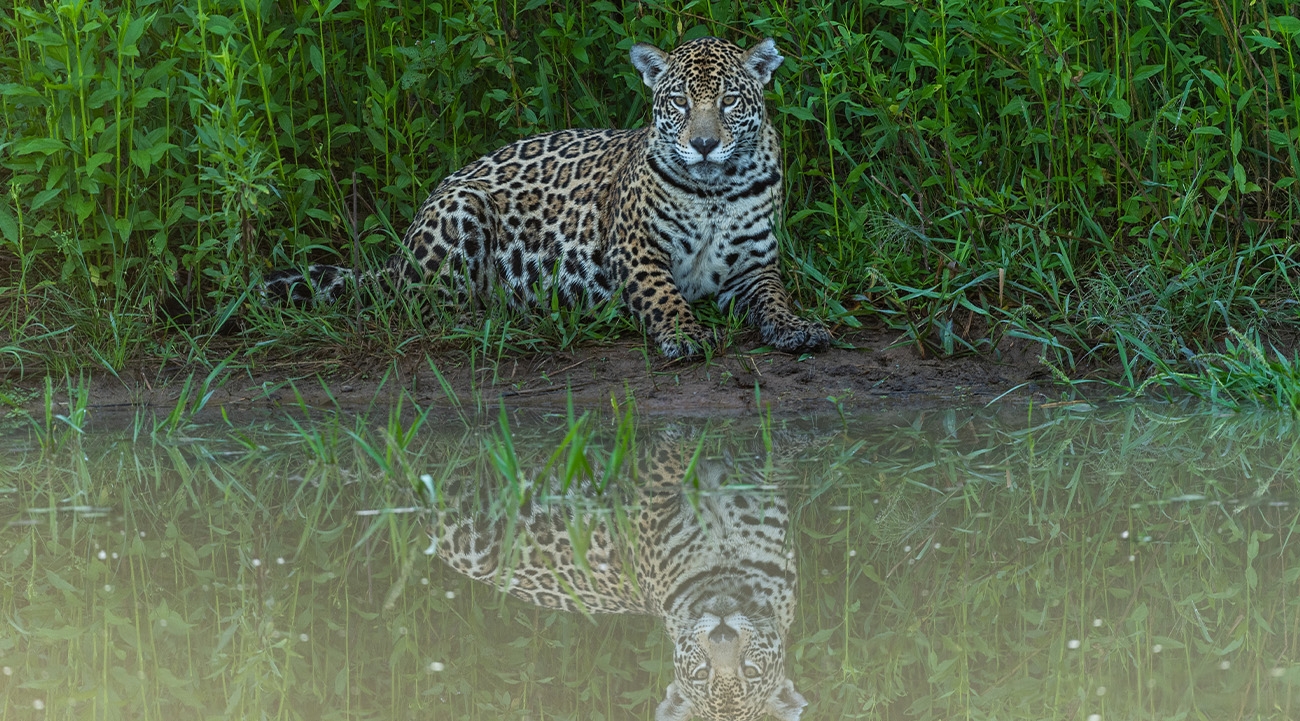

But not every animal we spot has a collar. On our way back to breakfast, we stumble upon young female Aracy admiring her reflection in a roadside pond. Mario draws a deep breath of excitement. Beyond demonstrating how easy it now is to see these animals even without the aid of technology, this sighting is especially significant.

Aracy, Mario explains, is the granddaughter of Isa, one of the orphaned jaguars Onçafari famously rewilded after a pioneering year-long project filmed by the BBC for a Natural World documentary narrated by David Attenborough. “Seeing this jaguar is even more special than seeing any other,” says Mario. “Mainly because she wasn’t supposed to exist.”

Although tourism is an important aspect of Onçafari’s work, their main focus is – and always has been – science. Back at their research base, Mario shows me clips collected on camera traps and runs through a series of presentations illustrating important findings made by the team that have led to the publication of academic papers.

“If you read any of the books, they say jaguars are solitary,” he says, referring me to footage of multiple jaguars sharing a carcass. “We also believe jaguars mate for pleasure or as a way to protect their young by distracting threatening males.”

Wildlife haven

Another fallacy exposed by both the team at Onçafari and Caiman is the belief jaguars can’t co-exist with cattle. According to Roberto Klabin, only 3% of cattle are lost per year to the big cats if the land is managed properly.

Driving to the outer fringes of the farm, I join Brazilian cowboy and pantaneiro farmer Seu Domingos Retiro Arara for a traditional rancher’s breakfast of manioc, minced meat, rice, beans and deep-fried cupa cheese bread.

He’s dressed in a straw hat with a knife hanging from the leather belt around his hips – a cowboy indeed. “Drought is the biggest problem we face,” he tells me through a translator, as we pick fresh fruit from an acerola tree. “Not jaguars.”

Thanking Roberto Klabin for teaching him about the value of these big cats, he says the wildfires raging across the Pantanal in recent years are a much bigger threat to his way of life.

Changes in climate have been impacting species across Brazil, making the work of conservationists even more vital. Back at Caiman, I visit the Instituto Arara Azul, an NGO set up by biologist Neiva Guedes to boost declining populations of hyacinth macaws.

Reliant solely on slow-growing, cavity-filled mandovi trees for nesting sites, the world’s largest parrot has become a victim of deforestation. Birds squark and squabble as field biologist Kefany Ramalho and her colleagues use ropes and harnesses to examine wooden nesting boxes erected in ‘surrogate’ trees.

To date, the project has been extremely successful: in the 20 years they’ve been operating at Caiman, the local population of hyacinth macaws has increased from 80 individuals to about 400.

In fact, wherever I go on the farm, wildlife is thriving. Marsh deer graze on meadows, giant anteaters snuffle through the long grass and even shy tapirs have gained enough confidence to emerge from forests at dusk.

It’s a safari on a scale that could easily match anything on offer in Africa. By laying a path for ecotourism in South America, Caiman has drawn international attention to a far-flung, challenging, but unquestionably beautiful, area that deserves to be on every wildlife lover’s map.

Book it: Abercrombie & Kent offers a seven-night trip to Brazil including five nights at Caiman Lodge from £6,999pp based on two people sharing. This includes flights, transfers, overnights in Rio de Janeiro, transfers and accommodation at Caiman Lodge on a full-board basis with all activities included.

abercrombiekent.co.uk